Steve Dillon is a British/Australian author who has also lived and loved on Vancouver Island for almost a year, and wishes it could have been longer. He now lives in Tasmania. Over the past few years, Steve has served up a recipe of more than 70 short stories and many poems, mostly of a dark flavour sprinkled with supernatural and psychological elements, and topped with a dash of surrealism at times.

Steve Dillon is a British/Australian author who has also lived and loved on Vancouver Island for almost a year, and wishes it could have been longer. He now lives in Tasmania. Over the past few years, Steve has served up a recipe of more than 70 short stories and many poems, mostly of a dark flavour sprinkled with supernatural and psychological elements, and topped with a dash of surrealism at times.

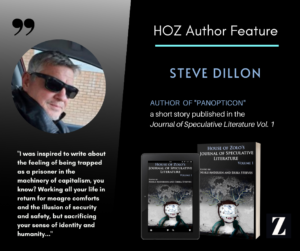

Steve is a contributing author to the House of Zolo’s Journal of Speculative Literature, Volume 1 with the short story “Panopticon.” Steve was kind enough to give House of Zolo this in-depth interview for our Author Feature series.

Was there a moment when you realized “I’m a writer”? Do you remember your very first story?

SD: I don’t recall my first story but it was at primary school, certainly. I loved writing short stories and was always thrilled to hear the teacher reading them aloud to the class, especially if one of mine was chosen. I can’t recall any of my own but I do recall another student’s piece being read aloud (Sandra Radford, whose younger sister Christine was in my class) who was no longer in the school. This was primary school, so I was about 9 or 10, and I thought, “Wow! If I can write like that, maybe my stories will be read after I’ve moved on.” I believe fundamentally this is partly what motivates many writers: to have your stories read and enjoyed after you’ve gone. My memory is flawed so this may not be correct, but the part I remember most from that story about a girl who was lost in the desert, and perhaps dying of thirst, was the line, “So I dived into the sand and swam home!” I often wonder if Sandra continued to write, but that line is so evocative and so surreal it blew my mind.

What inspired your dystopian story, Panopticon?

SD: For a while the working title was The Watchers Watched and that reflects the essence of the story at one level. I was motivated to write a Lovecraftian themed anthology set in the near future, and I was inspired to write about the feeling of being trapped as a prisoner in the machinery of capitalism, you know? Working all your life in return for meagre comforts and the illusion of security and safety, but sacrificing your sense of identity and humanity while ‘working for the man.’ I’ve worked for Microsoft on and off for 30 years, so this probably seeded some of these sentiments. That and the knowledge that if we’re lucky, and conform, we might be well catered for so long as we don’t pry too deeply or try to peer behind the curtains to see who (or what) is pulling the strings. The box in the story was a plot device really to seed the feeling of paranoia—never sure whether you’d be rewarded or punished as you respond to changes, all at the whim of the masters. And the conveyor belt thing—my ‘Soylent Green’ moment if you like, just mirrors the thought that eventually we are chewed up and spat out, to be fed back into the machine.

Do you have favourite subjects when writing fiction? What draws you to the speculative realm?

SD: We’re all inspired by what we read, and I still read a lot of Clive Barker, Ramsey Campbell, and to a lesser extent HP Lovecraft, and many others who excel in dark fiction. So, I invariably stray to similar subjects such as the paranoiac thoughts, whispers, and psychological terrors of Campbell, the cosmic horrors and conspiracies told of by Lovecraft, and the sex-and-death, beauty-and-beast, bland-and-beautiful imagery of Barker. If I have ever come close to emulating or reflecting my thoughts and ideas with anything like the mastery of these iconic creatives, then I am a happy person indeed. I can’t be drawn away from these themes for long, despite trying (and it’s the same with my painting by the way, which is darkly surreal).

Has your writing practice or subject matter changed during the pandemic?

SD: I published two anthologies (Infected 1 and Infected 2, both for the Save the Children Coronavirus Response) during the worst of the pandemic here on this little island called Tasmania, which only lasted a couple of months, amazingly, thankfully. We were largely spared by location and geography, and some good luck, I feel. So, my writing and my reading matter changed for a while at least while I was reading submissions and editing the book. If not changed completely, it certainly, honed in on specific aspects, such as the fear that grips each and every one of us since COVID-19—the fear of infection and sickness and premature death; of our lives being controlled by obscure laws and ambiguous rules for our own protection; of having to evolve and conform to new patterns of social behaviour, safety in isolation, and so on. My short story Panopticon also reflects these feelings, although of course it was written and published some time before then.

You ran a publishing company, Things in The Well, for some time—what led to your decision to move on? Do you have any advice or insight to share with independent publishers out there?

SD: I edited and published 28 books under Things in The Well, all dark fiction and poetry, and many of the titles also included stories I wrote in that time (including two collections). So I guess above all I was burnt out, and these things don’t really make much money (many of the titles were for charity, which do make more money thanks to the generosity of the authors and artists involved). Meanwhile, the work effort and the time these consume is tremendous and when you add to that the normal (and sometimes extraordinary) pressures of everyday life, family, work, and of course COVID-19, I decided to pack it all up after I’d fulfilled all my obligations to my friends, authors, editors, etc.

What projects are you working on these days? Feel free to share any links, etc.

SD: Although I’ve drawn a line under Things in The Well and the publishing venture and charity books, I haven’t stopped writing. In fact I’ve since self-published a collection of dark poetry called Last Moments of Bliss and Other Empathies. It’s more of a vanity thing I suppose, although you can find it on Amazon and here in the libraries in Tasmania at least. Ironically, the titular poem is about me leaving behind my writing, much of which was set in the fictitious town of Bliss… But of course you can’t just stop writing once you get the bug. I’ve said several times that “not reading, not writing, is like not seeing, not being able to speak,” and that’s how I still feel. I have a collection that’s almost ready to publish, Unholy Beginnings and Unhappy Endings, and another collection that’s a good way to completion. Then I have a novella I wrote at a writing retreat I was awarded here in Tasmania last year. And I have at least one novel in the works, which is more of a psychological/crime thriller. Who knows if they will ever see print? I’d like them to see something put out by a large publisher, so just like Sandra, perhaps I can be remembered after I’ve left this place.

Buy House of Zolo’s Journal of Speculative Literature, Volume 1